In the vast depths of art history, alongside the well-known names of Leonardo, Titian, and Caravaggio, who have become household names, there lies a sly group of artists who once enjoyed a notable slice of attention among specialists, gallery owners, collectors, and enthusiasts of all levels. Although today they may be largely unfamiliar to most, a prominent position in the hit parade of the 1500s was held by the so-called anticlassicists—a company of eccentric painters, often with Western European tastes, who ignited the Renaissance along the Po Valley, moving along the main routes that connected the northern part of the peninsula to Italy’s great centers of painting.

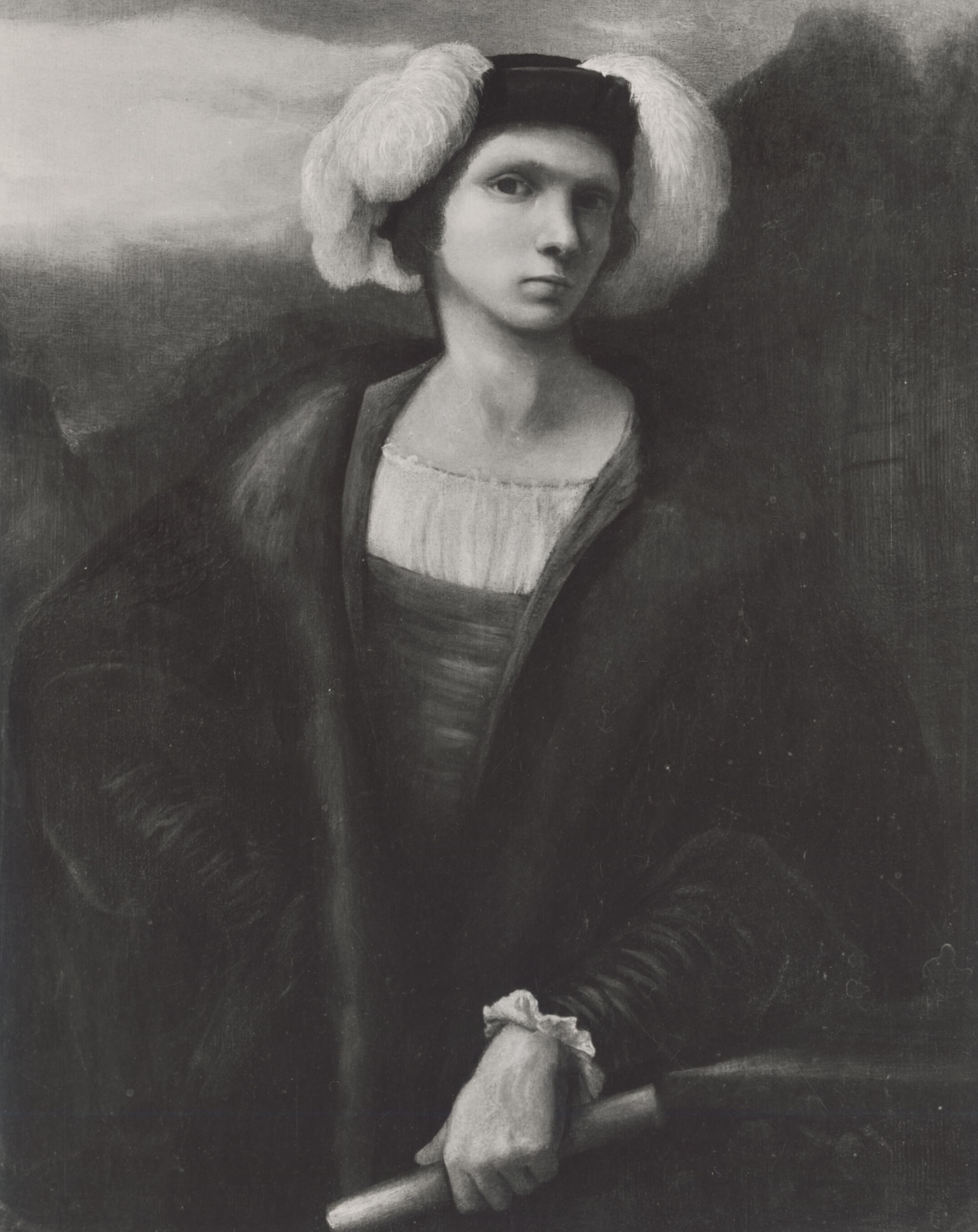

Dusting off these fine LPs, it is natural for those who remember them to wonder what became of artists as illustrious as Gianfrancesco Bembo and Altobello Melone. This Cremonese duo, starting in 1515, participated in the cycle of Scenes from the Life of the Virgin and the Passion of Christ by leaving their mark on the walls of Cremona’s Cathedral, creating a veritable manifesto for the anticlassical movement. How is it that masters capable of capturing the interest of generations of connoisseurs for more than a century vanished without leaving the faintest trace? For Bembo, the electrocardiogram is flat: not a single auction listing since the 1970s, when Finarte in Milan exhibited a somewhat rude-looking youth, which disappeared as swiftly into obscurity as it had materialized.

Were it not for the intriguing Lady with Poodle uncovered a few years ago by Maurizio Canesso, Gianfrancesco Bembo might be considered an extinct species rather than merely endangered. For Altobello, however, the scenario looks slightly different, as auctions suggest there may yet be a glimmer of hope. But is that really the case?

As is often the case, appearances are deceiving. When examining auction results from recent decades, we find a rather “interesting” story. Standing out among the copies and dubious pieces is a Madonna attributed to Altobello’s early maturity—a literally untouched, unpublished, electric, and alluring panel that appeared at Christie’s in London in 2019 with a relatively modest estimate given its rarity (£40,000), likely affected by its imperfect condition.

Moral of the story? Unsold. It would seem that collectors, aware of the topic’s specificity, prefer safer investments, securing masterpieces with a pedigree for relatively reasonable sums, such as the caustic Adoration of the Christ Child in the historic Lechi collection in Brescia or the volcanic Resurrection of Christ, discovered in 1950 by Luigi Grassi, who highlighted it in a foundational article on the painter.

But even here, are we truly certain? The flimsy foundation of this assumption is revealed by another Madonna, this time on canvas, published seventy years ago by Ferdinando Bologna and resurfacing at a Sotheby’s auction in London in 2006, where it sold at the minimum estimate (£80,000, equivalent to around €120,000 at the exchange rate of that time). After spending fifteen years in the Alana Collection in Newark, New Jersey, the painting reappeared at Sotheby’s in New York in 2021, with an astonishingly halved estimate (around €50,000). In less than two decades, this work has lost half its value, a decline not easily attributed to mere market strategies. Whatever the case, the result is indisputable, as once again the dreaded hammer of the bought-in fell mercilessly on the lot.

Given this worrying overview, one might assume that the champions of anticlassicism have lost the appeal that, despite their intrinsic rarity, studies and the market granted them in the latter half of the last century. Yet, we cannot simply explain this by attributing it to a general change in taste or blaming a waning interest among collectors. Ignoring the case of Dosso Dossi, a standout figure recognized even by those outside the anticlassicism niche, often due to the prestigious provenance of his masterpieces, we need only turn to the other great protagonist of this period, Girolamo Romani of Brescia, better known as Romanino. Merely observing the years 2023-2024 illustrates how the situation around Romanino differs greatly from that of Bembo and Altobello. This is evidenced by two previously unknown works: the late, evocative Deposition, sold by Bertolami in Rome for half a million euros (expenses included), and the youthful, incisive Christ Patiens, offered by Matteo Lampertico at the recent Florence Biennale of Antiquarians; not to mention the notable return of the Good Samaritan, formerly in the Roman collection of Pietro Toesca, recently acquired by the Tassara Foundation for MITA, the International Museum of Carpets in Brescia.

These new findings and rediscoveries are not merely exceptions to the rule but rather indicators of a consistent interest in the Brescia school of 16th-century painting. This interest is largely due to an admirable policy of cultural promotion and enhancement over the years, recognizing the role of Brescia’s Renaissance icons as guardians of a collective identity and investing in research on old masters against the tide. The exhibitions held in the city of Brescia from 2000 onward are evidence of this, showcasing a wide range of artists and converging contexts while remaining distinctive. From Vincenzo Foppa (2002) to Girolamo Romanino (2006), from Titian (2018) to Lattanzio Gambara (2021), and even exploring specific social settings as if captured in a still frame around a single figure—such as the current exhibition at the Museo di Santa Giulia, an elegant showcase centered on Fortunato Martinengo, immortalized by Alessandro Bonvicino, known as Il Moretto, in a marvelous portrait on loan from the National Gallery in London.

And in Cremona? True to tradition, it’s all fog and obscurity. Despite advancements in research, the last exhibition dedicated to the Campi family and Cremona’s 16th-century artistic culture was held in 1985—a fact well-known and requiring no further commentary. If there is demand, there can be supply, but it is also true that demand can be cultivated, as our beloved influencers have demonstrated—whether we like it or not. Let us not forget that any form of interest, whether economic or cultural, can be encouraged through cultural policies that embrace, promote, and support research, dissemination, and presentations of our heritage. Even in the third millennium, amid the rise of technology and artificial intelligence, it remains possible to work in this direction in unison: scholars and universities, institutions and foundations, collectors, and the art market. All of these actors, though with varying objectives, can align towards a common goal.

In short, it is time to cast the spotlight back onto anticlassicism through a renewed class action. Only by doing so will it be possible to foster new opportunities to rehabilitate these forgotten protagonists of painting in the Po Valley. Perhaps, finally, they may return to top international rankings. Altobello Melone and Gianfrancesco Bembo have wandered too long through the vast, desolate plains of the Po Valley, reduced to obscure figures, like uncredited cameos in a silent film from the early 20th century. It’s time to pry open the rusty gates of this chapter in art history and restore the anticlassicists to their deserved dignity. Let the safari begin.

13 November 2024