Inti Ligabue is the heir to a dynasty that has intertwined entrepreneurship, culture, and a passion for discovery for generations. It all began in 1919, when his grandfather Anacleto, a First World War veteran and railway waiter, transformed a military canteen service into a pioneering naval catering company. In the 1960s, his son Giancarlo took the reins, expanding the group beyond national borders and launching a second “empire” in parallel: that of scientific exploration. Over his lifetime, Giancarlo financed more than 130 archaeological expeditions across five continents and built a unique collection. In 1973, he founded the Ligabue Study and Research Center, which today, under Inti’s guidance, has become the Giancarlo Ligabue Foundation — a unique institution in Italy promoting research and dissemination in paleontology, archaeology, and ethnology. Like his father, Inti now leads Ligabue Spa, supporting research while pursuing a passionate approach to collecting that bridges past and present. He discusses this in the following interview.

Let’s start from the beginning. You are one of the few Venetians born and raised in Venice who still live in the city.

I was born in Venice on April 17, 1981, to a Bolivian mother and a Venetian father, Giancarlo Ligabue. My parents met in Rome while my mother was working at the FAO, and not, as many might think, in the Amazon rainforest because of my father’s explorations. I feel deeply Venetian—so much so that I’ve never left the city—but my South American roots are something I feel deeply. They are not just my origin but an intimate and authentic dimension, reflected in my passion for pre-Columbian cultures. My name, Inti, means “Sun God” in the Quechua language and is still widely used in Bolivia and Peru.

When did your interest in collecting begin? I wonder if the first object you desired was pre-Columbian…

I grew up surrounded by art and diverse cultures, but my passion for art and beauty emerged when, as a young boy, I began digitizing my father’s archive: letters, catalogs, and handwritten notes—at that time, there was nothing electronic. As I studied the extraordinary network of relationships that connected Giancarlo to the greatest European merchants and gallery owners, I felt a deep and osmotic call. But the first item in my collection wasn’t pre-Columbian; it was African. Eighteen years ago, I was searching for a KOTA reliquary in Gabon, Africa, but I was struck by a PUNU mask: white, made of kaolin, with an almost oriental face and a timeless beauty. It was love at first sight; I bought it without even negotiating the price.

To what extent do you think your father influenced your journey as a collector?

In reality, there has never been a true handover. My father was already fifty years old when I was born. He has always been a researcher and explorer, ever since he decided to fund the excavations led by Philippe Taquet, which led to the discovery of two dinosaurs. One of them is now on display at the Natural History Museum of Venice, named after Giancarlo. Throughout his life, he supported hundreds of archaeological expeditions worldwide, and his collection has always been dedicated to research and scientific production. It was a project deeply focused on study. My path, on the other hand, is characterized by a more informative vocation.

Was there a specific moment when you developed this awareness?

Yes, in 2015, when I presented part of my father’s collection at the Archaeological Museum of Florence, in the pre-Columbian art exhibition The World That Wasn’t There, alongside masterpieces from the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris and other prestigious international collections. My father had recently passed away, and that exhibition may have symbolically marked a handover. I vividly remember the moment I walked into the galleries and saw the objects on display, arranged by culture and artistic style. I felt their intensity — and realized they could no longer remain confined to a private setting. They had to be shared. Since then, through the Giancarlo Ligabue Foundation, we have promoted exhibitions in major museums around the world, with the aim of spreading knowledge of tribal, pre-Columbian, and African cultures. That is the essence of my approach to collecting today.

A form of collecting, then, focused on dissemination and sharing. Are you inspired by anyone in particular?

Yes, I deeply admire figures like the Rovati family (Luigi Rovati Foundation), who have successfully built a collection that is eclectic, coherent, and open — and who have chosen to make it accessible to the public through a museum. It’s a model that strongly resonates with me, and one I intend to follow in the future headquarters of the Ligabue Foundation, which will be housed on the first floor of Palazzo Erizzo in Venice. In both collecting and curating, I don’t favor geographical or chronological classifications, but rather seek to foster dialogues between forms, concepts, and geographies.

Beyond the desire to share, is there something else that drives you to collect?

I vividly remember an episode from my childhood: I was in Olduvai, Tanzania, in the Rift Valley — the birthplace of the Homo genus — together with my father and Donald Johanson, the paleoanthropologist who discovered Lucy. As we walked, I came across a peculiarly shaped stone, drop-like in form: it was a quartz hand axe, dating back around 7,000 years. It’s known that the earliest Homo sapiens — and perhaps even the australopithecines — collected hand axes and singularly shaped stones. Even Tutankhamun was a collector of walking sticks…

As a child, I understood that collecting is something ancestral. It’s not mere obsession or accumulation. We, as collectors, must be poetic storytellers for these cultures and these objects. Because some of them are universal — they strike chords we can’t fully describe. And in the end, they choose you, not the other way around.

It seems that this dimension of transcending cultures, places, and times lies at the very heart of your collection. Can you tell us about it, and describe how it has evolved from your father’s?

Giancarlo’s interest began with classical antiquity — Rome, Greece, and Etruria — and expanded in the late 1960s with the acquisition of a Teotihuacan mask, which sparked his passion for pre-Columbian art. This interest deepened with the acquisition of the Venere Ligabue, a female Bactrian idol from the 3rd millennium BCE — a unique piece, paired with a sister sculpture now housed at the Miho Museum in Japan. The collection then grew to include Mesopotamian, ethnographic, and tribal art.

I have since broadened its scope further, following the trajectory set by my father but also incorporating works on paper, drawing, Venetian painting (both historical and contemporary), and photography. Today, the collection spans a vast arc — from the earliest symbolic expressions of the Paleolithic to the most abstract forms of contemporary art.

Is there one work in your collection that holds particular significance for you, both artistically and emotionally?

Without a doubt, the Grotesque Head attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, authenticated by Luisa Cogliatti Arano and featured in the exhibition De’ visi mostruosi at Palazzo Loredan. It represents a journey through Leonardo’s use of deformed faces to study human emotion, as noted in the Codex Atlanticus. My father purchased it as a “drawing from the Milanese school” — a choice guided by his eye, not by academic credentials. That intuition is what every collector should strive to cultivate. I hope to continue developing it and to let that attentive gaze guide my future collecting choices.

What are your most recent acquisitions?

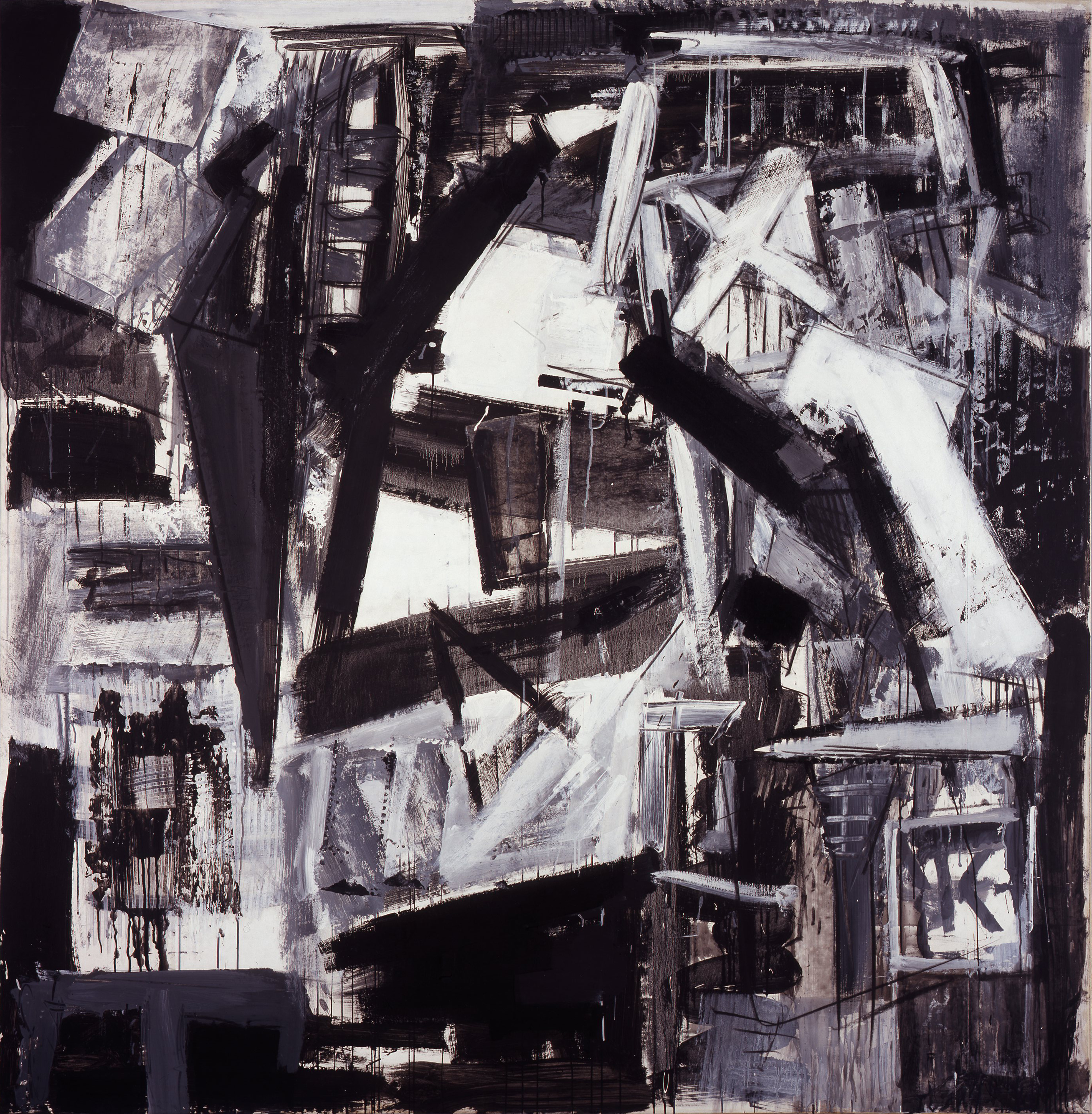

A Flute Stopper from Biwar, an Aripa from the EWA culture, a beautiful Dogon maternity figure, and a 1957 work by Tancredi.

When did you first open up to collecting modern and contemporary art?

My interest in contemporary art began when I read the Spatialist Manifesto of 1947. That’s when my passion for the Venetian Spatialists was sparked — artists like Bacci, De Luigi, Rampin, Santomaso, Tancredi, and Toffolo. I love Venetian artists for their ability to translate a unique quality into painting: the light reflected off the water.

Today, I follow contemporary art by supporting artists connected to Venice, such as Giorgio Andreotta Calò, Marta Spagnoli, Chiara Enzo — but also Nico Vascellari and Vera Lutter. I collect their work and, where possible, try to accompany them on their path, while recognizing that the primary role in that process belongs to the galleries.

Are galleries the main channel through which you acquire works? Or do you also attend fairs and auctions?

I have longstanding relationships with a few gallerists, built on trust and deep friendship. I often travel to visit international art fairs — my favorite is TEFAF Maastricht, which is unique in the chronological breadth it offers: eight thousand years of history under one roof.

I also buy through auction houses, which now dominate the market thanks to their global reach and marketing strategies. But auctions often strip the acquisition of that romantic, intimate dimension, and leave a permanent mark on the object — for better or worse. I continue to prefer galleries that guarantee the quality, conservation, and authenticity of a work. It’s a model that deserves to be protected.

I imagine you have an ongoing dialogue with art critics and historians.

Absolutely — that’s an essential part of the process. Over the years, we’ve worked with leading scholars, beginning with Pietro Marani, a great expert in drawing; with Steven Hooper, a specialist in Oceanic art; and with André Delpuech, a renowned curator of pre-Columbian arts, formerly at the Musée du Quai Branly and later at the Musée de l’Homme.

Each of them brings scientific rigor, passion, and a curiosity that inspires and supports our publications and exhibitions.

One last question: how do the roles of Inti the collector and Director of the Ligabue Foundation coexist with that of Inti the entrepreneur?

One buys, the other pays! Joking aside, it’s a dynamic balance, where each role supports the other. The collector and cultural promoter in me nurtures the desire for research, discovery, and deeper knowledge — that’s where it all begins. The entrepreneur helps organize and sustain everything, turning passion into projects, exhibitions, and donations, and ensures that the cultural and scientific legacy of the Ligabue family continues to live and grow over time.

22 July 2025