It is hard to exaggerate Senator Giovanni Falier’s merits with regard to Canova in that crucial period stretching from Canova’s early training as an artist to his departure for Rome. Falier detected Canova’s talent when he was still only a young lad and acted to ensure that he could serve his apprenticeship in Giuseppe Bernardi’s workshop in Pagnano d’Asolo; he hosted him in Venice after Bernardi’s death and introduced him into the Venetian society; he commissioned his first marble works; and he facilitated the commissioning of the Daedalus and Icarus group that allowed him to set his sights on Rome. The entire decade, as difficult for the artist as it was crucial to his development, clearly unfolds around Falier, to whom Canova was to continue to express his most sincere gratitude until the very end of his career (1). Nor was the bond that he forged with the Senator’s son Giuseppe (Iseppo) any less intense or significant. Iseppo was almost the same age as Toni, the friendly name by which he addressed the artist in his prolific correspondence with him. Their particularly close relationship was forged in their childhood, when the Falier family spent a great deal of time in their villa near Pradazzi, just outside Asolo. This deep friendship between men so different in their social status and their lives yet who shared their love of art, was to spawn the biography of Canova that Iseppo published in 1823, only months after his friend’s death (2). After Paravia’s timely yet partial Notizie (3), this was the first of many biographies of the artist but it differs from the others in that it offers a first-hand view of events permeated by the close friendship that existed between the biographer and his subject. The source is particularly important for Canova’s adolescence and apprenticeship.

Iseppo Falier was a meticulous and reliable witness of the period in which Canova took his first steps in carving stone under the guiding hand of his stern grandfather, Pasino. Pasino, like Canova’s father Pietro who died prematurely in 1761, practiced the most customary of trades in this region in the foothills of the Dolomites stretching from Pove to Pederobba, where droves of stonecutters had scraped a living for centuries from the marble quarries. Far more than a mere stonecutter though, Pasino “practiced architecture… exercised draughtsmanship… busied himself with adornment, and with excellent taste” (4). This mingling of the skills of the stonecutter and the architect, the very skills that formed such

great artists as Palladio and Piranesi, allowed Pasino to rise above his station and to work on building altars, miniature architectural constructions spangled with semi-precious stone inlay and finely carved altar frontals, thus dipping more extensively into the world of sculptural architecture and stone decoration (5). In his abbozzo di autobiografia (outline for an autobiography) Canova himself mentions that his

grandfather “showed great talent and skill in his architectural works, and in a few small works of sculpture”, instilling in his grandson “unbelievable enthusiasm, especially for the latter” (6). Falier’s long standing familiarity with the Canovas accounts for the protection afforded young Antonio. Iseppo writes: “My father was very fond of Pasino, very often keeping him busy with work in his profession” (7). Pasino had indeed played a far from negligible part in improvements to the Faliers’ villa complex near Pradazzi, Federici even arguing that he “renovated and extended” the building – although, in reality, that role had fallen to Giorgio Massari, at least as far as the chapel and the right wing are concerned (8). But therecan be no doubt that, after working with his son Pietro on carving architectural elements in Crespano del Grappa cathedral (designed by Massari), Pasino also worked for the Senator. His grandson’s lively intelligence and aptitude for sculpture, soon perceived by Falier, prompted the Senator to persuade Pasino to allow the promising youngster to train far more profitably under the guiding hand of a skilled sculptor. Just such a tutor happened to be at hand. Giuseppe Bernardi was a sculptor of some repute in Venice and he was the nephew and heir of Giuseppe Torretti, the founder of the glorious sculpting

tradition in Pagnano d’Asolo. Bernardi, who had moved back from Venice to his native Pagnano some years earlier, working intensely in the region’s churches, had been offered a demanding commission by the Senator c. 1766–8 closely associated with his plan to renovate the Pradazzi villa, involving the installation of a substantial number of garden statues (which were sold off in their entirety in the mid-20th century, when the Falier family no longer owned the property). It is worth dwelling on this project, not simply because Canova himself was commissioned to complete it with statues of Eurydice and Orpheus between 1774 and 1776 – his earliest known figurative works to date (9) – but also because it was through these statues in Vicenza stone that the extremely young sculptor began to familiarise with a genre which had not been part of his skill set until then, drawing inspiration from them that was reflected in the early part of his career. Antonio Muñoz saw ten of the statues lining the avenue leading up to the villa in 1924 and he mentions some of the subjects portrayed (10). Five of the statues recently surfaced on the antique market, albeit wrongly attributed to a Lombard sculptor (11). Two of them, among the best known in the series and also published by Semenzato in 1958 and 1966 (12), depict Paris and Helen, while the others portray Hera (in poor condition but identifiable by the peacock accompanying her), Aphrodite and Athena. Thus they tell us that Falier commissioned Bernardi to depict the Judgment of Paris in its entirety, a worthy emblematic conclusion to a cycle built around thetheme of love and beauty in mythology. It is easy to identify the sculptor’s typical style of the late 1760s – rounded heads with hair pinned up, and drapery with gentle, classicising folds yet rich in detail and with an exuberant tone hinting at the Rococò – a contention borne out by comparison with the allegories he carved for the Great Gatčina Palace in 1766 and with his St. George carved for the Doge’s Palace in 1769 (13). The reconstruction of the

Judgment of Paris in Pradazzi is endorsed by Antonio Massari when, among Bernardi’s works in Villa Falier, he lists the statues of Minerva (Athena) and Juno (Hera) standing close to the barchesse, thus only a short distance from Paris and Helen who stood “to the west, in an isolated kiosk” (14).The chance to view them more clearly today makes it even easier to understand Canova’s words when, thirteen days before dying, driven by nostalgia, he and his friend Iseppo Falier visited the villa’s park and the places they had known in their childhood: “And yet they have merit! See, see how delightfully graceful they all are” (15). Those statues, though no longer fashionable, and alien to Neoclassical taste, sparked in the artist a sentiment that transcended his objective judgment but that certainly shows no sign of the irony or haughtiness that people have deliberately sought to detect in those words (16).

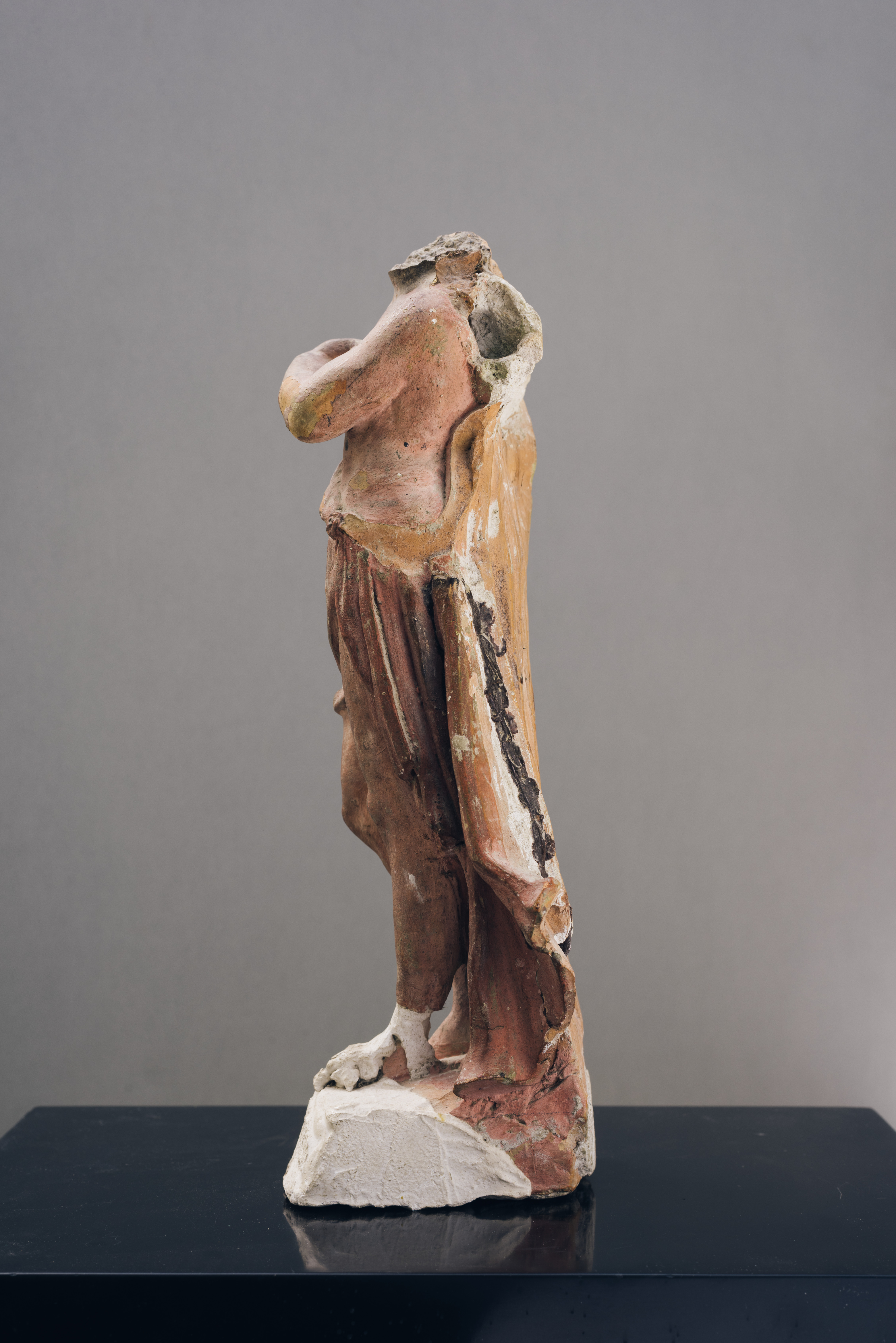

While Falier’s role in entrusting young Canova into Giuseppe Bernardi’s care “as though he were his own son” 8 (17) is beyond question, it is still useful to remember that Pasino had already had the opportunity to work on the projects in which Bernardi had been involved, and that the two men are therefore highly likely to have enjoyed a certain working relationship, looming in the background of which we can frequently detect the figure of Giorgio Massari. In addition to the villa near Pradazzi, it is also worth examining, in this connection, a selection of works in the churches of Crespano del Grappa, Galliera Veneta and Asolo. The high altars in Galliera and Asolo, in particular, reveal the involvement of both workshops, with Pasino producing altars in the Roman style and Bernardi’s workshop responsible for the marble Angels in Adoration, which de facto emulate the extremely high-quality angels in Crespano cathedral (18). All these circumstances are of crucial importance in connection with our analysis of the clay sculpture under discussion in this essay. The sculpture in question is a headless Angel

in Adoration devoid of its wings and a part of its right arm, completed in a sensitive and respectful ‘restoration’ to which we shall be returning in the course of the essay (19). The figure stands out, in its formal and typological characteristics, from a direct comparison with Bernardi’s repertoire (20). The inclination of the neck and the slight twist of the bust tell us that the angel was designed to stand on the obsever’s left and that it was accompanied by a second figure that must have been a mirror image of it. The arms ritually crossed on the breast, the counterpoise of the limbs, the ephebic body in slow rotation and the tunic tied on one side by a graceful rosette-shaped clasp, leaving the left-hand thigh bare, are convincingly, yet only partially, echoed in the angels that Bernardi carved for the altars in Saonara, Galliera Veneta and Crespano del Grappa (21). The terracotta does not, however, point to a direct relationship with any particular one of Bernardi’s numerous Angels in Adoration, and while its parentage is undeniable, it does not show the kind of close interdependence that one would expect between a finished work and its preparatory model. What does characterise the sculpture, on the other hand, is its drier, more stringent spirit, its different, tighter handling of drapery, where work known to be by Bernardi or reasonably attributed to him invariably displays a handling of drapery that is still Baroque in feel, more generous, occasionally even excessive, and designed to impart a dazzling painterly effect to his marbled tunics and flowing marble veils. None of Bernardi’s angels leaves its limbs as bare, yet the influence of his models is

so clear in the sudden flow of the fabric on the left leg that it is reminiscent of the fluttering

vents of the angels mentioned above. The history and paternity of the terracotta under discussion suddenly become clear in the light of a passage in Canova’s memoirs written by Iseppo Falier. The biographer, a direct witness to the artist’s apprenticeship in the workshop in Pagnano d’Asolo, mentions a number of otherwise unknown episodes in his effort to highlight Canova’s precocious progress. For example, he tells us that his young friend made him a gift, despite his “few short moments of study” so far, of “two drawings of casts or models… a Bacchus and a Venus… made when he was no older than twelve” (22). This is followed by the passage that concerns us directly. “Several months thereafter, he fashioned two Angels in clay with such ease and such mastery that he astonished his own teacher, and his family rejoiced with great pleasure”.

The family members to whom Falier alludes included, in particular, Canova’s grandfather, Pasino, whose involvement the author goes on to explain in detail: “These two small models,” he tells us in a note, “later served his grandsire to carve the two angels of the high altar in Monfumo in pietra dura stone, as we said” (23). The terracotta under discussion here matches in every way – save for its far loftier quality – the sculpture on the left of the high altar in the church of San Nicolò in Monfumo, a charming village perched on a hill midway between Castelcucco and Asolo. The Angels, carved in stone, are not in the best condition because they were removed in 1934 and placed outside the building at the entrance to the priest’s house. They were then moved again several times before finally being reinstated in the church, but the result of an attempt to repair the damage caused by the elements by painting them over proved to be even worse than the damage itself (24). The Angels’ harsh execution reveals the hand of Pasino, who lacked experience as a figure carver; and indeed scholars’ opinion of them is unanimous and has been reiterated again only recently on the basis of a very reliable source (25).

According to Falier’s reconstruction of events, Canova’s terracottas were probably fashioned when he was about thirteen, thus c. 1770. Sources that mention the Monfumo sculptures, on the other hand, offer us no clearly defined evidence, and Don Basso’s contention that they were made in 1763, thus three years after the new church had been completed (26), is likely to refer to the altar rather than to the later Angels. This contention appears to be borne out by Falier’s attribution to him of two stone figures rather than of

the altar itself, given that he does (tentatively) attribute to him the altars in “Tiene, Galleria, s. Vito” (27). The altar’s marble structure does indeed differ from Pasino’s work, which is more in tune with Massari’s classicism, and while this consequently points to the involvement of two different artists, it also gives us good reason for arguing that the two Angels were fashioned at a later date. The importance of Falier’s precise account, which has been confirmed again very recently (28), sits in the strictly biographical nature of his memoirs, their validity opportunely underscored by Giuseppe Pavanello: “…recounting the facts, including the smallest details, in the artist’s life” (29). And now, the discovery of one of the terracottas comes to confirm – if there were any need – the validity of that historical source, because what the

clay Angel implicitly tells us perfectly mirrors Iseppo’s reconstruction, with the gruff grandfather praising his nephew “with such great pleasure” that he even translated into stone, as best he could, his nephew’s youthful yet already impressive exercise in the sculptor’s art. Falier’s dogged determination to cling to the facts, and the interest he displays solely in “first-hand stories resting on guaranteed facts” (30), can also be clearly seen in his decision to abstain from recording romanticised or totally unfounded anecdotes

regarding the adolescent artist’s early career, for example the improbable “tale of the lion

cub in butter” that Federici includes in his Memorie Trevigiane (31). We now need to interpret and carefully analyse Pasino’s execution of the Angels against the backdrop of Canova’s biography. Iseppo rightly informs us that Canova fashioned the Angels c. 1770, 1771 at the latest, in other words, shortly before he moved to Venice with Bernardi. Perhaps, had Canova not followed his master to Venice, the Monfumo Angels might have been his first essay in monumental sculpture, though we know that that

honour actually falls to the Eurydice which Senator Falier commissioned from him in 1774 and which he mentions in 1787 as “my first large statue from life” (32). Canova’s silence on the very early terracottas in the “Notes of Antonio Canova on his own works”, however, comes as no surprise. In those notes he lists his “statues” in the strictest sense of the term. He makes the significance of the list quite clear by failing to include in it the Fruit Basketsthat he carved for Daniele Farsetti, thus he was even less likely to include two small clay Angels modelled when he was still only a lad. It is common knowledge that the period preceding the commission of the Eurydice for the villa in Padrazzi is somewhat unstable in terms of definite chronological references. It all depends, so to speak, on the date Canova’s apprenticeship with Giuseppe Bernardi actually began. If we read his friend Iseppo’s memoirs, Canova must have been about twelve and thus he would have followed his master to Pagnano in 1769, immediately after the Pradazzi commission. This dating is accepted in the life penned by Antonio d’Este (33), while the anonymous Abbozzo di biografia and Melchiorre Missirini, on the basis of those notes, push the date back by one or two years, arguing that he was apprenticed to Bernardi “at the age of 13 to 14 years” (34), thus between 1770 and 1771. Now, while these differences are deserving of attention, they in no way affect the case under discussion in this essay, and there can be no doubt that we are looking at Canova’s first work, whether he fashioned it at the age of thirteen or fourteen, after a year’s apprenticeship in which he had made progress “without first engaging in the usual studies” (35), in other words without first undergoing academic training. It was in the dusty workshop in Pagnano that Canova “began to work on things in relief on Torretti’s models”, as Melchiorre Missirini (36) specifies in a remark that defines the exact context of the rediscovered terracotta.

What we are looking at here is an extremely young Canova expressing his talent by revisiting his master’s teachings with intelligence and with his own temperament. Far from offering us a mere novice’s first attempt, Canova revisits a Pagnano workshop model with a certain independence of spirit, possibly still a little immature but already imbued with that sensitivity that was to characterise the statues he carved for Falier, and which is in any case a far cry from Pasino’s harsh technical and formal style. What I mean is that

while we can, of course, detect the influence of Canova’s training in Asolo in it, the drier, more slender conception of the figure’s anatomy and the form of its drapery, devoid of Bernardi’s somewhat affected and overloaded exuberance, point to a far plainer and more concentrated approach heralding his future development in Venice. The polished anatomy, the placid flow of the fabric devoid of all painterly effect and a certain enlargement of the figure’s right hand are all aspects that underscore the extremely young artist’s characteristics and personality. These characteristics also appear to point to an awareness of that trend in 18th century Venetian sculpture that was based on an early fascination with the ancient world and that was fated to have a beneficial, if indirect, impact also on Canova (37). I wonder, on a more specific note, whether Canova’s Angel may not also reveal the influence of the statues of Antonio Gai and, more especially, of Giovanni Marchiori – for instance, the latter’s Angels

in Adoration in Corbanese and Sant’Ambrogio di Fiera (38) – in other words, the two most important exponents of that learned classicising tendency. The numerous and invariably lofty works of Marchiori disseminated also throughout the Treviso area were certainly within reach of a brilliant and inquisitive young artist of Canova’s calibre and he cannot have been indifferent to them, judging by the rhythm of the Angel in Adoration which is, naturally, receptive to Bernardi’s teaching but which, at the same time, is far more stringent and far calmer. Canova’s calm nature, his failure to be fully convinced by his

master’s “grace”, can also be detected in Pasino’s stone version, through his grandson’s mediation. While bearing in mind the merciless simplification and the limitations of the Monfumo statues, the Angel on the right, for which we are missing the model by Canova on which it is based, undoubtedly harks back to Bernardi’s prototypes. The arms held away from the breast, the hands joined and the vents opening up above the knees take us back to the Angels in Adoration in Saonara, Asolo and Crespano, yet we can detect an unquestionable independence of style in the tight-fitting vest that leaves the shoulders

bare, and in the more concise handling of the drapery. Continuity with Bernardi also shines through very clearly in the technique adopted to fashion the terracotta. It hardly needs pointing out that we are not dealing here with the meticulous models of Canova’s mature years, the instantaneous compositions designed to capture only his initial figurative idea ahead of some large, carefully fashioned plaster

models39, but rather at the kind of clay model typical of 18th century Venetian sculpture that is well represented by the many surviving examples of Giovanni Maria Morlaiter (40) and by what Bernardi himself had learned from his uncle Giuseppe Torretti (41). The sources rightly indicate that this was the path that Canova was to follow also in fashioning the preparatory models for his Orpheus and Eurydice which he fashioned partly from life in his home in Possagno (42).

What does seem appropriate to highlight is that the dawning moment to which this early work by Canova belongs lies completely within the furrow of the loftiest Venetian tradition embodied by Bernardi. Canova had not yet spent months attending the Accademia’s school of nude figure drawing, where he was to forge an important bond with the painter Giambattista Mengardi, or familiarising in depth with the prototypes of classical statuary in Filippo Farsetti’s collection. It is in that light that we can explain the specific nature of the terracotta Angel, its unique place in the young sculptor’s career. In cultural terms, it is worlds apart not only from the innovative group of Daedalus and Icarus but even from the statues of Orpheus and Eurydice that so clearly display their intelligent affinity with Mengardi’s models and their utterly new approach to the painterly nature of Venetian sculpture, favouring a more limpid conception of volume (43). Yet the work under discussion here is not isolated in any restrictive or negative sense, because in the way the limbs are turned, in the way the tonal transitions flow so delicately, in the

sensitive definition of the right foot, we can detect encouraging similarities with the Apollo

in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, a terracotta fashioned by Canova in 1778 for one of the statues for Ludovico Rezzonico’s villa in Bassano del Grappa and donated to the Accademia by the sculptor in person in April 1779 (fig. 12) (44).

The Apollo is, of course, a far more mature piece that also reveals the influence of Bernini, whose work Canova saw in the Farestti collection, but if we hold it up against the light, we can still detect traces of a certain continuity with his earlier work. By the same token, in fact possibly to an even greater extent, the Angel’s anatomical structure, its high waistline and rounded hips, appear to offer us a foretaste of the figure of Eurydice that Canova carved in 1774, at an even earlier date than his Apollo. In any event, it is clear that both the Eurydice and the Accademia Apollo mark a turning point, the moment when Canova left behind him the crucial influence of Bernardi that still informs the terracotta Angel. The solidity and persistence of the manner of Canova’s first master in his young mind can be demonstrated not only through what we learn from the sources but also through a close inspection of his work. We have seen the extent to which our Angel echoes the style of Bernardi’s marble statues. Now we can explore its similarities with his terracotta works, an aspect that testifies in full to his formative and technical background. In order to do this, we can begin by analysing two interesting clay sculptures by Bernardi, which I myself discovered and have discussed in a different context (45). Analysing them here, in the context of Canova’s earliest work, is interesting on several counts, particularly if we consider that

they share the same provenance as the Angel in Adoration and that, like it, they too show evidence of later restoration and of being given a whitish patina attributable to the same hand, as we shall see below. We should also remember that, as things stand today, we know of no other models or bozzetti definitely by Bernardi. This, because we have no choice but to exclude from his catalogue the emphatic, rough terracottas depicting the Evangelists in the Birmingham Museum of Art (46) , alleged to be models for the statues in Santa Maria della Fava but which in reality show only superficial compositional similarities and no true stylistic connection with Bernardi’s work. The first – headless – terracotta that we shall discuss in this connection portrays St. John the Baptist (47), as revealed by his characteristic, untanned camelskin tunic. Caught just below the waist, it leaves his right side bare while covering his right shoulder, its solemn drapery reaching down to the ground. The compositional syntax of the figure’s limbs is reasonably similar to that of the Angel in Adoration with the arms crossed over the breast: the sole surviving features of the left hand are the phalanxes of some of the fingers clinging to the bust. The counterpoise of the lower limbs is discreet, almost as though seeking to hint at the saint’s solemn gait, with a basically frontal view contrasting with the slight twist of the bust. This terracotta is the preparatory model for the statue of St. John the Baptist adorning the high altar of the church of San Giovanni Evangelista in Travettore, near Rosà, along with a second statue depicting St. Benedict. We know very little about these two marble statues, which bear absolutely no relation to the Neo-Gothic church built between 1912 and 1926 and which now adorn an equally 20th century altar (48), but while the statues’ clearly erratic provenance fails to offer any evidence for their material history or origin, the church’s proximity with Rosà, of which Travettore is a suburb, does appear to offer us a significant clue, given that Giuseppe Bernardi worked

there extensively. The surly St. Anthony the Abbot and St. Spyridion on either side of the high altar in the cathedral, commissioned from Bernardi on 30 July 1763 (49), display similarities with the Travettore statues both in their solemn, academic design, which is particularly evident in St. Bendict’s episcopal attire, and in the frowning, grumpy look on their faces framed by snakelike beards. They also show evident formal and typological similarities with the statue of St. Paul in Resana, which displays the same emotional density with the sudden rotation of the head and the gesture of the arms aligned on the

breast. The proud expression of St. John the Baptist, with that neo-16th century mood that characterised Venetian sculptors with a classicising bent in the 18th century (50) – particularly Bernardi’s uncle, Giuseppe Torretti – and the full, intensely drilled locks, reveal close similarities with the Angels in Adoration in Crespano del Grappa, carved in 1762, persuading us that the Travettore statues also belong to Bernardi’s later output. We are now in the late 1760s, when Canova was already serving his apprenticeship in the master’s workshop, which not only explains the clay Angel’s extremely strong similarities with St. John the Baptist in the shape of his very short tunic, but also establishes another concrete reference for the young Canova’s design.

The last and most badly damaged bozzetto in the group, devoid not only of its head but also of its base and feet, depicts Apollo (51), as we can tell from the lyre on which the god of music and poetry rests his left hand. We should note that the flattening of the back and the white finish match the figure of St. John the Baptist, while Canova’s Angel, on the other hand, tends to develop the drapery on the back more fully and also reveals a different degree of finish on the back, which is less rough and furrowed by long parallel lines. This, without overlooking the fact that Canova’s youthful Angel reveals a calmer

approach, while Apollo and St. John the Baptist show a quicker, more nervous hand, pointing to Bernardi’s maturity and greater experience. In terms of comparisons, which are less simple to make on account of Bernardi’s more limited catalogue in the field of garden sculpture, it is neverthless of interest to note both the echo of the statues in Pradazzi, which we now know at least in part, and of the allegorical figures in the Great Gatčina Palace, on account of the meticulous and graceful drapery, of the broad composition and of the solid yet relaxed anatomy.

While we cannot rule out the possibility that the terracotta may be the preparatory model for the Apollo carved for Senator Falier, a statue which has yet to be tracked down, we are still talking about the late 1760s, probably shortly before Bernardi’s definitive return to Venice. This circumstance would appear to help explain the reason why two of Bernardi’s terracottas shared the same fate as a youthful work by Canova, fashioned in the very years in which he was serving his apprenticeship in the master’s workshop.

This brings us to a point of the greatest interest, namely the sculptural completion, in both the Angel in Adoration and St. John the Baptist, of the bases (52) and the areas that might have jeopardised the figures’ stability, particularly that of the Angel: the calf and left foot, the right shoulder and where the wings join the body.

This singular and respectful ‘restoration’, which fails to make good the most obvious losses – the head, arms and hands – reveals the peculiar characteristics of Canova in the fullness of his maturity and points us in the direction of clear comparisons with numerous autograph bozzetti (53). The casual, rapid use of the wooden shaper and the artist’s fingers on the damp matter, the dripping, almost organic technique making the anatomy of the foot shorter and more slender, are features that de facto characterise the instant bozzetto of the Three Graces in the Museo Civico in Bassano del Grappa, modelled in 1812 (54). But equally instructive comparisons can be made with the back of the Allegory of Painting in

the Monument to Titian in Possagno or with the plaster Hector in the Museo Correr, fashioned from 1808 onwards (55). Thus the Angel in Adoration, the artist’s first documented work, offers us an absolutely singular, or rather a unique, instance of Canova restoring his own work decades later. It is absolutely plausible that he returned to these works – fashioned when his talent was still budding and doubtless filled with memories for him – when he returned to Possagno in July 1819 to lay the foundation stone of the Tempio (56). Where else, if not in the house in which he was born in Possagno, could the Angels in Adoration be stored after grandfather Pasino had used them for his statues in Monfumo? Naturally, the fact that two models by Giuseppe Bernardi were moved from Pagnano to Possagno and into Canova’s hands is not nrecorded, but the repetition of that gentle ‘restoration’ on the figure of St. John the Baptist and its identical provenance are the most eloquent evidence for such a move. The home of his grandparents and his father, his home, was the setting in which the loving npreservation of a few fragments of his youth was played out in an instant. The deepest sense of the man’s nature lies in this act, if it is true that “there has perhaps never been an artist more devoted and bound to his birthplace than Antonio Canova” (57). In the sculptor who picks up the living remnants of the past and becomes the guardian of his own roots, we can grasp the sense of the message transmitted in his final wishes, directed totally towards the completion of the Tempio di Possagno, a monument that was to impart greatness to his tiny native village: “this is the mark and the significance of my work, from here I set out, and here amongst you I return” (58). Leaving and returning – a return that was not physical, or not only physical – to which Canova bound our understanding of his life and of his career as an artist. The terracotta modelled in his early youth is, at the end of the day, itself a metaphor of this circular trajectory that joins the beginning to the end: departure and return. The Angel contains within it Canova the Venetian, a child of his land, and Canova the ‘universal’ artist, a father of his time, the last giant in Italian art. I would like to express my gratitude to: Fr. Paolo Barbisan, Fr. Gaetano Borgo, Fr. Marco Cagnin, Monica De Vincenti, Simone Guerriero, Barbara Guidi, Andrea Nante and Claudio Seno.

Ed. Editor’s note: This study, resulting from the expertise requested from the author by Galleria Gomiero following the discovery of the work in question, was originally published in Arte Veneta 80/2023, Electa, 2024, pp. 246 et seq.

1 G. Pavanello, L’elogio di un “uomo veramente perfetto”, in G. Falier, Memorie per servire alla vita del marchese Antonio Canova [1823], anastatic edition ed. G. Pavanello, Bassano del Grappa 2000, pp. XVIII-XIX.

2 For the relationship between the biographer and his subject, see R. Pancheri, Iseppo Falier, amico e biografo di Canova, in G. Falier, Memorie per servire, op. cit., pp. XXIII-XLV.

3 P.A. Paravia, Notizie intorno alla vita di Canova, Giuseppe Orlandelli Editore, Venice 1822.

4 G. Falier, Memorie per servire, op. cit., p. 8.

5 C. Pegoraro, “…Antonio Canova, nativo di Possagno nel Triviggiano…”, in Canova, exhibition catalogue (Bassano del Grappa, Museo civico; Possagno, Gipsoteca), ed. S. Androsov, M. Guderzo, G. Pavanello, Geneva-Milan 2003, pp. 45-47; E. Catra, in E. Catra, V. Pajusco, Antonio Canova nel Veneto. Itinerari, p. 55 cat.

7 F. Leone, Antonio Canova. La vita e l’opera, Rome 2022, pp. 19-20.

6 A. Canova, Scritti, I, ed. H. Honour, P. Mariuz, ed. Rome 2007, p. 332. In connection with Pasino’s sculptures, see the continuation of the text, esp. note 25.

7 G. Falier, Memorie per servire, op. cit., p. 8.

8 A. Massari, Giorgio Massari architetto veneziano del Settecento, Vicenza 1971, p. 88.

9 M. De Grassi, in Canova, op. cit., p. 356 cat. IV.2.

10 A. Muñoz, Il periodo veneziano di Antonio Canova e il suo primo maestro, “Bollettino d’arte del Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione”, 18, 1924-1925, pp. 105-107; according to the author, the four pairs depicted “Diana and Endymion, Hercules and Omphale, Apollo and Daphne and another two statues whose subject was unclear to me; while in another part of the garden there is a group depicting Helen and Paris”.

11 Milan, Il Ponte auction house, 28 March 2023, lot nos. 17, 129-131. Apart from myself, Monica de Vincenti also identified Bernardi’s works and will be communicating her findings shortly. After this text was submitted for publication (April 2023), the discovery was published by G. Pavanello in Statue del giardino di villa Falier ai Pradazzi di Asolo transitate in asta a Milano, “Ricche minere”, 19, 2023, pp. 167-171.

12 C. Semenzato, Giuseppe Bernardi detto il Torretto, “Arte veneta”, 12, 1958, pp. 174-175; Id., La scultura veneta del seicento e del settecento, Venice 1966, pp. 65, 139-140, figs. 216-218.

13 See, in addition to the bibliography mentioned, also M. Klemenčič, Giuseppe Bernardi, in La scultura a

Venezia da Sansovino a Canova, ed. A. Bacchi in conjunction with S. Zanuso, Milan 1999, pp. 695-696. Equally significant is a comparison of the Falier statues with the Noblemen dressed as gardeners and hunters in Villa Pisani in Stra, for which Bernardi received a payment in 1769. See S. Guerriero, in Per un Atlante della Statuaria Veneta da Giardino, ed. M. De Vincenti, S. Guerriero, “Arte veneta”, 65, 2008, pp. 280-283.

14 A. Massari, Giorgio Massari, op. cit., pp. 88-89. According to Massari, relying on unspecified sources, Bernardi Torretti’s works were even greater in number. Along the avenue he records another pair of statues depicting Bacchus and Ariadne (possibly the very same ones that Muñoz found difficult to identify), while the pillars at the gates of the property have allegories of the Four Seasons resting on them. We cannot rule out the possibility that these Seasons may have been by a different hand, possibly by his uncle Giuseppe Torretti, given that Falier himself (Memorie per servire, op. cit., p. 5) mentions “several sculptures by talented Artists [Torretti uncle and nephew]”.

15 G. Falier, Memorie per servire, op. cit., p. 9, note 2.

16 C. Semenzato, Giuseppe Bernardi, op. cit., pp. 175-176.

17 G. Falier, Memorie per servire, op. cit., p. 9.

18 See C. Semenzato, La scultura, op. cit., pp. 139-140; A. Massari, Giorgio Massari, op. cit., pp. 35, 67-68; C. Pegoraro, “…Antonio Canova, nativo di Possagno nel Triviggiano…”, in Canova, exhibition catalogue (Bassano del Grappa, Museo civico; Possagno, Gipsoteca), ed. S. Androsov, M. Guderzo, G. Pavanello, Geneva-Milan 2003, pp. 45-48.

19 The terracotta, 33.4 cm. high, is covered in a pinkish varnish echoing the colour of terracotta and has

extensive traces of dark wax on its sides.

20 The perception of these typological features underpins the attribution which I initially formulated in favour of Bernardi “despite the terracotta not being precisely related to any of Giuseppe’s works”. G. Sava, “Abbozzare con fuoco ed eseguire con flemma”. Antonio Canova e tre terrecotte di Giuseppe Bernardi, in Canova tra innocenza e peccato, exhibition catalogue (Rovereto, MART), ed. B. Avanzi, D. Isaia, Rovereto 2021, p. 46.

21 The articulation of the arms, in particular, is based on the left-hand Angel in the Cathedral of Crespano del Grappa –the angel on the right of the high altar in Saonara, on the other hand, inverts the arms’ overlap – while the shape of the rosette by the vents is based on the right-hand Angel in Galliera Veneta.

22 G. Falier, Memorie per servire, op. cit., p. 10.

23 Ibid.

24 M. Basso, Monfumo. La storia, i luoghi, le opere, Asolo 2002, p. 18.

25 See M. Pavan, Canova, Antonio, in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, 18, Rome 1975, p. 197; G. Pavanello, L’elogio di un “uomo veramente perfetto”, p. XI; M. Basso, Monfumo, op. cit., p. 18; C. Pegoraro, “…Antonio Canova, nativo di Possagno nel Triviggiano…”, op. cit., p. 46; E. Catra, in E. Catra, V. Pajusco, Antonio Canova, op. cit., p. 55 cat. 7; F. Leone, Antonio Canova, op. cit., p. 24. The Angels’ leathery modelling reveals similarities with the Bust of the Virgin in rilief in Villa Falier in Pradazzi, traditionally attributed to his grandfather: A. Muñoz, Il periodo veneziano, op. cit., pp. 104, 122. Antonio d’Este also mentions a “small marble Madonna” in Canova’s home attributed to Pasino: A. d’Este, Memorie di Antonio Canova, Florence 1864, p. 2.

26 M. Basso, Monfumo, op. cit., p. 18.

27 G. Falier, Memorie per servire, op. cit., p. 8.

28 C.D. Dickerson II, E. Bowyer, A passion for clay, in Canova. Sketching in clay, exhibition catalogue (Washington, National Gallery; Chicago, Art Institute), ed. C.D. Dickerson II, E. Bowyer, Chicago 2023, p. 18: “two angels in clay that later served Pasino in carving the decorations for the high altar of a church”.

29 G. Pavanello, L’elogio di un “uomo veramente perfetto”, op. cit., p. XXI.

30 Ibid.

31 D.M. Federici, Memorie trevigiane sulle opere di disegno. Dal mille e cento al mille ottocento per servire alla storia delle belle arti d’Italia, Venice 1803, II, p. 193; G. Pavanello, L’elogio di un “uomo veramente perfetto”, op. cit., p. XIII. For the vast figurative as well as literary echo of this legendary episode, see G. Pavanello, L’ultima leggenda: il leone di burro, in Canova gloria trevigiana. Dalla bellezza classica all’annuncio romantico, exhibition catalogue (Treviso, Musei civici), ed. F. Malachin, Crocetta del Montello 2022, pp. 31-45.

32 It is the list drafted by the artist in 1787, i.e. the “Notes by Antonio Canova on his own works”: A. Canova, Scritti, op. cit., p. 260.

33 A. d’Este, Memorie di Antonio Canova, op. cit., p. 5. His loyal pupil set the start of his apprenticeship “in

November 1768 or 1769”.

34 A. Canova, Scritti, op. cit., p. 332; M. Missirini, Vita di Antonio Canova Libri quattro, ed. J. Bernardini, Rome

2016, p. 47. He is inclined to set the start of the apprenticeship in 1770–1, F. Leone, Antonio Canova, op. cit., p. 20

35 A. Canova, Scritti, op. cit., p. 332.

36 M. Missirini, Vita di Antonio Canova, op. cit., p. 47.

37 See in this connection M. De Grassi, L’antico nella scultura veneziana del Settecento, in Antonio Canova e il suo ambiente artistico fra Venezia, Roma e Parigi, ed. G. Pavanello, Venice 2000, pp. 35-69; M. De Vincenti, “Piacere ai dotti e ai migliori”. Scultori classicisti del primo ‘700, in La scultura veneta del Seicento e del Settecento. Nuovi studi, Seminar proceedings (Venice, 30 November 2001), ed. G. Pavanello, Venice 2002, pp. 221-281 (esp. pp. 239-248); S. Guerriero, M. De Vincenti, La scultura. Antonio Gai, in Anton Maria Zanetti di Girolamo. Il carteggio, ed. M. Magrini, Verona 2021, pp. 211-225.

38 See S. Guerriero, Nuove proposte per Giovanni Marchiori (1696-1778), in Francesco Robba and the Venetian Sculpture of the Eighteenth Century, International conference proceedings (Ljubljana, 16 – 18 October 1998) ed. J. Höfler, Ljubljana 2000, pp. 127-132.

39 Definitely see H. Honour, Dal bozzetto all’”ultima mano”, in Antonio Canova, exhibition catalogue (Venice, Museo Correr), ed. G. Pavanello and G. Romanelli, Venice 1992, pp. 33-43; also H. Honour, Canova’s Work in clay, in Earth and Fire. Italian Terracotta Sculpture from Donatello to Canova, exhibition catalogue (Houston, The Museum of Fine Arts; London, Victoria and Albert Museum, 2001-2002), ed. B. Boucher, New Haven 2001, pp. 67-81. Now also see in connection with these aspects C.D. Dickerson II, E. Bowyer, A passion for clay, op. cit., pp. 9-47.

40 See in this connection M. De Vincenti, Catalogo del “fondo di bottega” di Giovanni Maria Morlaiter, “Bollettino dei Musei Civici Veneziani”, 6, 2021, pp. 12-77.

41 As one can deduce, for example, from Giuseppe Torretti’s terracotta depicting St. Andrew, a model for the statue in the Basilica of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice: M. De Vincenti, L’”ingegnosissimo Torretti scultore”. 1664-1743, in Revixit: un capolavoro intagliato di Giuseppe Torretti restaurato da Venetian Heritage, exhibition catalogue (Venice, Palazzo Grimani), ed. M. Clemente and M. De Vincenti, Venice 2020, pp. 24-25.

42 As narrated in the greatest detail by M. Missirini, Vita di Antonio Canova, op. cit., p. 50. See in connection with these events F. Leone, Antonio Canova, op. cit., p. 31.

43 For relations with Mengardi and the similarities between the Orpheus and the Expulsion of Cain painted by Giambattista in Campagna Lupia in the early 1770s, see F. Leone, Antonio Canova, op. cit., pp. 32-33.

44 It is common knowledge that the statues were never finished and the only ones that were rough-hewn

were destroyed shortly afterwards. For the Apollo see G. Pavanello, in Antonio Canova, op. cit., p. 159, n. 77; F. Leone, Antonio Canova, op. cit., pp. 40-41; C.D. Dickerson II, E. Bowyer, A passion for clay, op. cit., p. 22.

45 G. Sava, “Abbozzare con fuoco ed eseguire con flemma”, op. cit., pp. 45-49.

46 C.D. Dickerson II, E. Bowyer, A passion for clay, op. cit., pp. 18-19.

47 The terracotta is 31.8 cm. high.

48 The statues may have been procured by the aristocrats Gino and Maria Zanchetta, munificent patrons of the church as recorded on a monument erected inside the church in 1946.

49 G. Mantese, Rosà. Note per una storia, Vicenza 1977, pp. 224-225.

50 M. De Grassi, L’antico nella scultura veneziana, op. cit., pp. 35-69; M. De Vincenti, “Piacere ai dotti e ai

migliori”, op. cit., esp. pp. 223-224, 228-236. The figure’s articulation also appears to reveal the influence of Antonio Tarsia, a sculptor with whom Giuseppe Torretti was closely associated.

51 Height 23.5 cm.

52 The Apollo’s more dilapidated condition, devoid as it is of a base and feet, probably accounts for the absence of any work on it in the 19th century, unless of course that work has since been lost.

53 Irreplaceable in this connection is H. Honour, Dal bozzetto all’”ultima mano”, op. cit., pp. 33-44; also H.

Honour, Dal bozzetto all’”ultima mano”, in Canova, op. cit., pp. 21-29. For Canova’s “sketches”, now see the Washington exhibition catalogue Canova. Sketching in clay, op. cit.

54 See G. Ericani, Il primo bozzetto delle Tre Grazie, in Canova, op. cit., pp. 31-35; Io, Canova genio europeo, exhibition catalogue (Bassano del Grappa, Musei civici), ed. M. Guderzo, B. Guidi, G. Pavanello, Cinisello Balsamo 2022, p. 274 cat. 122; C.D. Dickerson II, E. Bowyer, A passion for clay, op. cit., p. 41.

55 For the Possagno bozzetto (no. 70), dated 1790–5 and more generally for the peculiarities involved in the execution of Canova’s terracotta works, see a very recent essay by A. Sigel, Reading Canova’s hand, in Canova. Sketching in clay, op. cit., pp. 223-241(esp. pp. 235-241; fig. 30 on p. 237). In connection with the Hector see G. Pavanello, in Antonio Canova, op. cit., p. 178, n. 92 and most recently C.D. Dickerson II, E. Bowyer, A passion for clay, op. cit., pp. 13, 38.

56 P.A. Paravia, Notizie intorno, op. cit., p. 44.

57 C. Pegoraro, “…Antonio Canova, nativo di Possagno nel Triviggiano…”, op. cit., p. 47.

58 Ibid., p. 45.

19 November 2025